For a long time and up to this day I miss my previous home and life on the shores of the awe inspiring Lake Tanganyika in ways that are hard to describe. Its grandeur and scale are hard to take in with pictures or words. Its name is means, ‘ a great lake spreading out like a plain.‘ It has a raw elemental power, as if it it is aware of its own life giving force and power that has existed in a great rift created millions of years ago in the centre of Africa.

The statistics give some clues. It is the longest freshwater lake in the world, the second oldest, second deepest and second most voluminous in the word to Lake Baikal. It holds 16% of the earths freely available freshwater, it covers an area of 32,900 square kilometres with an estimated volume of 18,900 cubic kilometres. It has its own endemic fish fauna which make the Galapagos look a like an impoverished cousin. It was the drama, freedom, many moods and scale of the place, not forgetting the diversity of its underwater life that attracted me and kept me there for so many years.

Although I was a foreigner to the lake I felt at home there, a place where I was comfortable and at ease, where I felt that I fitted in more as seasons and time passed by. Looking back it was sense of feeling naturalised, of being comfortable in your own skin and in tune with your surroundings. Whenever I left the lake for a period of time, whether it was for a day or two or maybe for weeks, I always felt a sense of relief driving back down the road to Mpulungu when the distant lake nestled in the great land rift would jump into view. This relief would grow when I had climbed onto the boat to take me ten miles across the water, back to the peace and tranquility of Tukulungu.

Over twenty-five years of living on the lake had convinced me that there was an awful lot of truth in the aquatic ape theory(AAT) and that our evolutionary past, our ability to walk and and subsequent development was closely linked with living near to water. The many thousands of hours diving underwater added to the fact that I had trained many indigenous people who were working for me to snorkel and use SCUBA gear to catch live fish had convinced me of this. Our combined underwater time amounted to many tens and probably hundreds of thousands of hours immersed in the lake, so whilst my beliefs maybe considered anecdotal they still provide evidence and can support the theory in many ways.

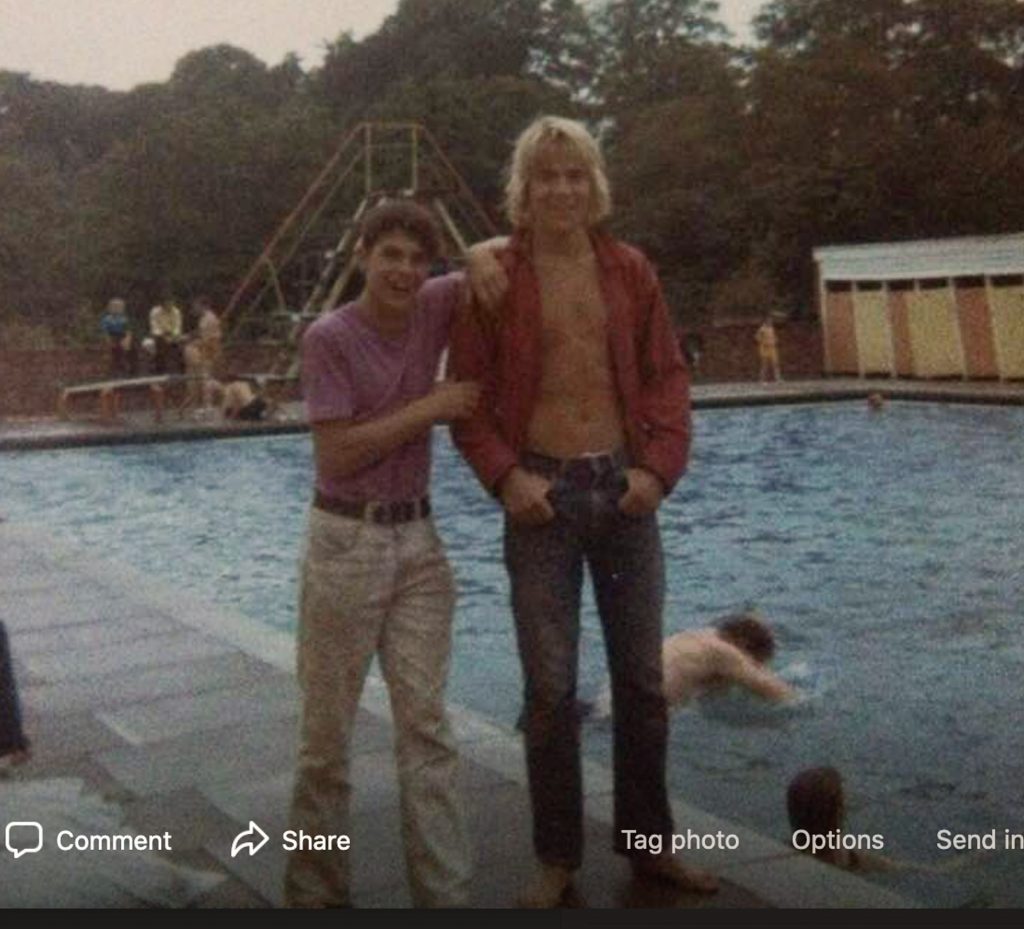

I have always been drawn to and attracted by water. I had learnt to swim at an early age in the local outdoor swimming pool whilst at primary school. Swimming lessons were a highlight of the week during the summer terms. Years later I was drawn back to the same Deer Leap swimming pool in the fine summer of 1973, where acting as a lifeguard seemed like a much better option than going to school to study for chemistry, physics and biology A levels. A couple of years later this vocational training paid off and I became Hertfordshire Mens Lifesaving champion, where the competition had drawn in packed crowds of exactly nobody. I would like to think it proved invaluable experience for where life was to lead me.

So many of us are instinctively drawn to water, to rivers, to lakes and to the sea. Vast numbers of people live in cities near the sea especially where major rivers meet the ocean. House prices are higher by the sea, by a lake or river (above reasonable flooding risk! ). People yearn to retire and spend their later years breathing sea air, walking on a beach and looking at ocean views. Millions of people chose to spend their holidays lying in the sun next to chlurine-filled (a chlorine and urine cocktail!) hotel swimming pool or on the deck of a cruise liner next to a pool whilst gazing at the open ocean. We are drawn to water by a seeming magnetic force, it appears to be embedded in our DNA. Water covers 70% of the earth. Two elements, hydrogen and oxygen, combine as 3 atoms in to make this vital life-giving molecule. From this apparent simplicity life on this earth depends.

It was only just over three years ago that I thought that the best and simplest antidote to missing the lake was to make a small pond. It also has to be right at the top of any list to attract wildlife to a garden. So it seemed like a winner on a number of levels; it would at the very least let me get close to some water with life in it, which I could touch and feel as well as just simply look at whilst seated in my wheelchair.

Once the decision had been made, I ordered a pond liner and Bob did the hard graft with a spade digging out the heavy clay and building-rubble that was buried in the small bank of grass where the pond was going to lie, on a couple of chilly January days in 2017. I had checked the council guidelines and was confident that a pond would be considered as a landscape feature and would therefore not need permission to have it in the garden. It was certainly not any of the alternatives that needed permission like a wall or a fence.

Remarkably frogs spawned in the pond a few weeks after the pond had been finished. I slowly accumulated different water plants to add into the water as well as planting around the pond itself. Life gradually moved in and established itself. Every year since it was first dug the variety has increased. Toads, palmate and smooth newts have joined the frogs in using the pond to spawn. Damselflies and dragonflies flit by on sunny days whilst the pond-skaters are ever present on the pond surface.

The pond contains around 1,000 litres of water which means that Lake Tanganyika could fill it around 17 billion times or have enough water to supply every human on earth water to fill three similar ponds. So whilst this pond maybe infinitessimally smaller in so many ways it still packs a mighty punch in the value that it brings to my life and the life that it attracts into the water and around it. Moving from a Great Lake in the Great African Rift Valley to a pond just demonstrates life’s dependence on water.