Except during the nine months before he draws his first breath, no man manages his affairs as well as a tree does

George Bernard Shaw

A brief background on the path to becoming a Wheelchair Gardener

Many of my earliest and clearest memories from my first years of life are from the outdoors. I can remember the hedge with the shiny green leaves on either side of the path right outside which led up into the woods from the house where I was born and then spent my first five years. It was in Hampstead Garden suburban in north London. My strongest memories of first school days were not the school itself, nor the teachers, nor other children, but finding a nest of baby hedgehogs in the ground right near the school gates. This was a source of surprise, but also a secret that could not be readily shared.

We moved from London, when I was six, to a small village in the Chiltern Hills with a big garden, a big oak tree and a field right next door, so that you could just jump over the gate and you could disappear off across the fields onto the nearby common. There always was something to do and places to explore. In the summer holidays you could disappear for the day, only to go home for food. Ashridge forest owned by the National Trust was not far away, and many happy days were spent playing and exploring where beech trees dominated and fallow deer, foxes and badgers had the run of the woods.

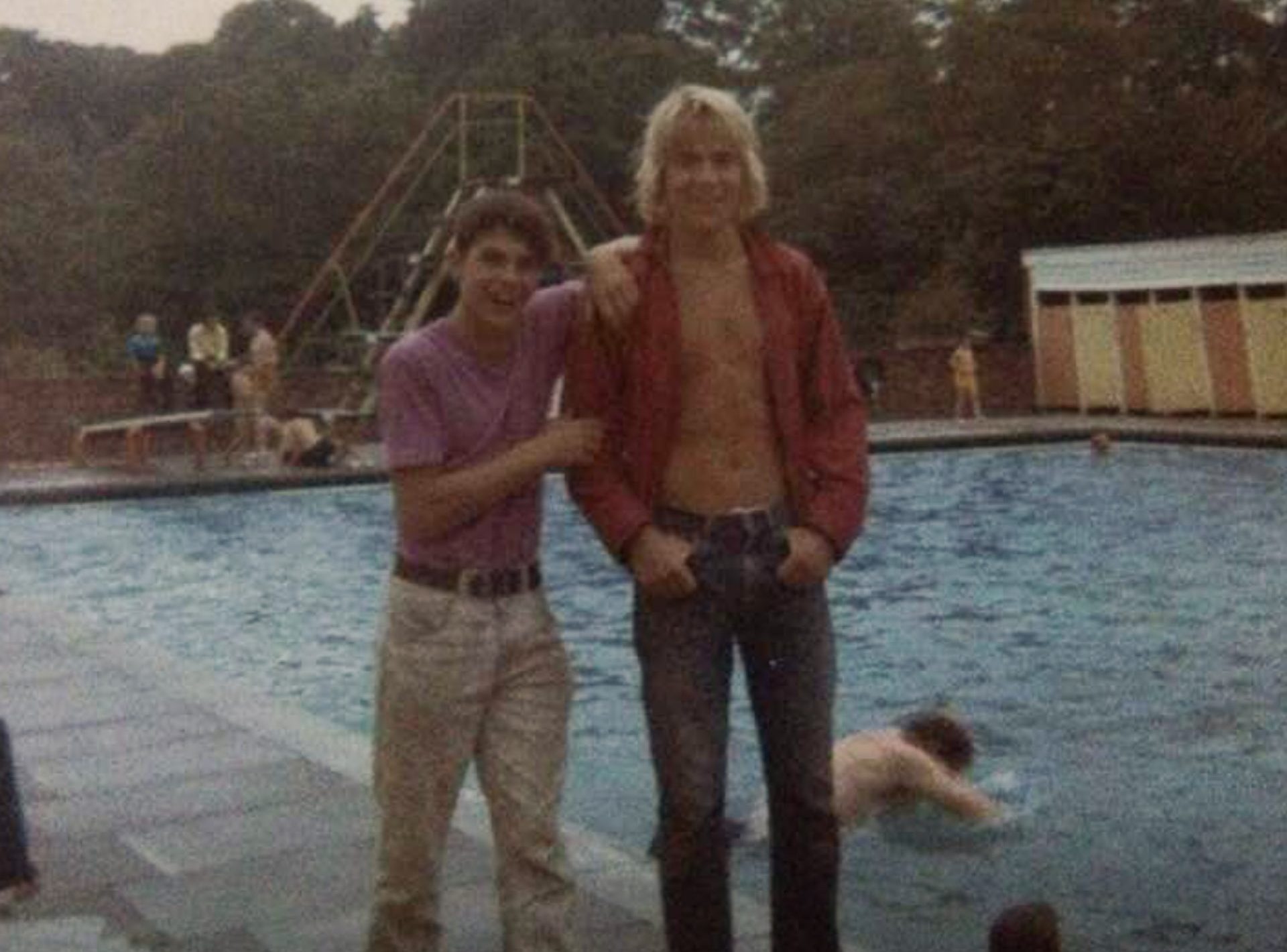

Secondary school was a grammar school a few miles away, with the 317 bus journey to and from the school, much of it passing alongside the River Gade. I passed my O levels, but it was in the lower sixth form that I decided it would be a good idea to go into school to register, and then to bunk off to the local swimming pool to work as a lifeguard, and when the sun set onwards to the pub, where I lied about my age to drink beer. This cunning ploy went undetected for a while until it was discovered and questions were asked, “What are you going to do with your life?” I did not have any clear answers ready to offer, so after some indecision I joined the police cadets.

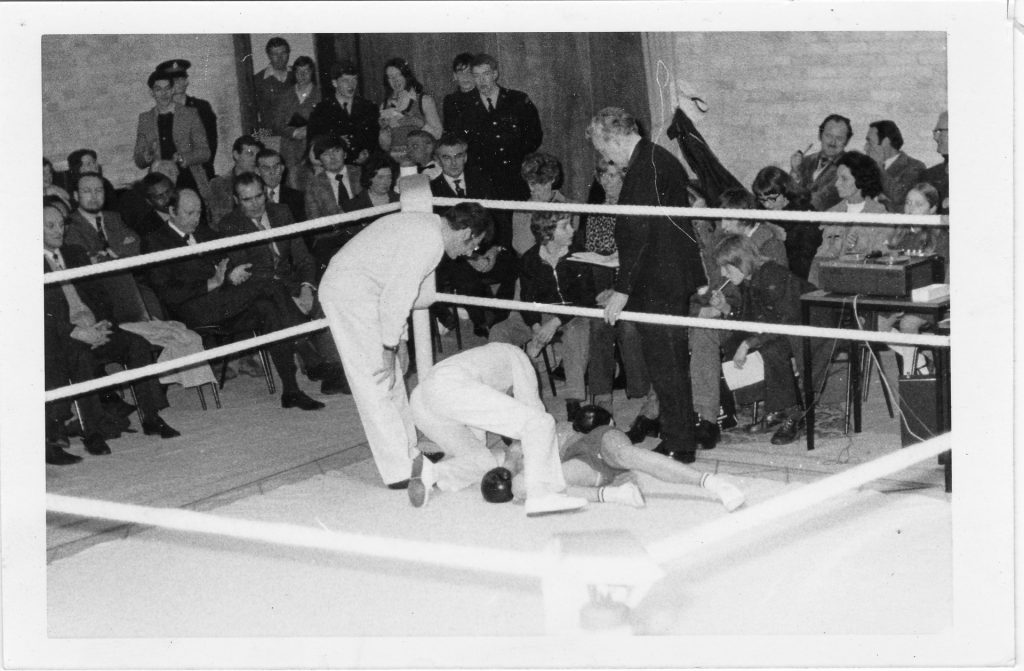

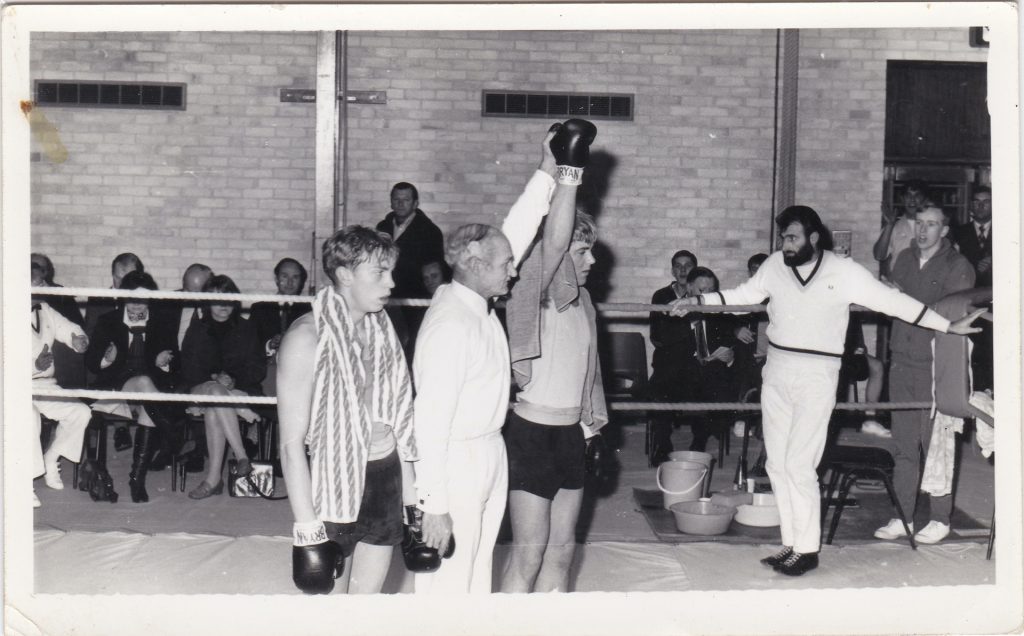

Life in the Hertfordshire Constabulary was a big change from school. I was away from home, earning money, playing lots of sport, some academic studies and a fair dose of discipline along with a short back and sides. Two years led to another choice, whether to stay in the police and have a career, or to go to university.

Whether by chance or by design I saw a prospectus for a course in Rural Environment Studies at Wye College in Kent, which was a part of London University. I set my heart on going there and was lucky enough to get a place on the course. In the late 70s those were the earlier days of modern environmentalism and conservation, with textbooks like Rachel Carson’s ‘Silent Spring’ (1962), and ‘Limits to Growth’ (1972 Meadows et al), it seemed then that the environment was going to be a major item on the world political, governmental and economic agenda.

This proved to be wishful thinking beyond belief, with the growth of consumerism, neoliberal-ism, globalisation, corporatisation and the god of economic growth becoming the all consuming goals. Three years went by and at the end of it I managed to come out with B.Sc(Hons) despite spending more time in The Honest Miller than the library by some margin, if my memory serves me right.

After leaving university I had landed a job with the BBC as the Animal Researcher for the third series of All Creatures Great and Small, about the life of the Yorkshire vet, James Herriot. In the space of two weeks I had gone from a penniless student, to a back pocket full of expenses cash and a Range Rover, to head off from London to the Yorkshire Dales to start locating the differ-ent animals needed for filming on location. At the end of the series, I began working freelance and was trying to find work at the BBC Natural History Unit.

Then the airmail letter from Zambia arrived, offering me a job as the Warden at the Outward Bound Lake School. This was a year after I had written to most of the Outward Bound schools around the world, and received mostly refusals with, “not enough job experience”. I made a fairly spontaneous decision to go out there and have a look, after I had looked up in the atlas to find out exactly where it was.

After spending a few months at the Outward Bound school, which was desperately short of money and was unable to pay my salary let alone other running costs, I found work as a walking safari guide in the Luangwa Valley National Park. A year or so of safari work passed in that wonderful place, which was a time when heavy commercial poaching had just started, but black rhino could still be found on foot, and it was known as The Valley of the Elephants.

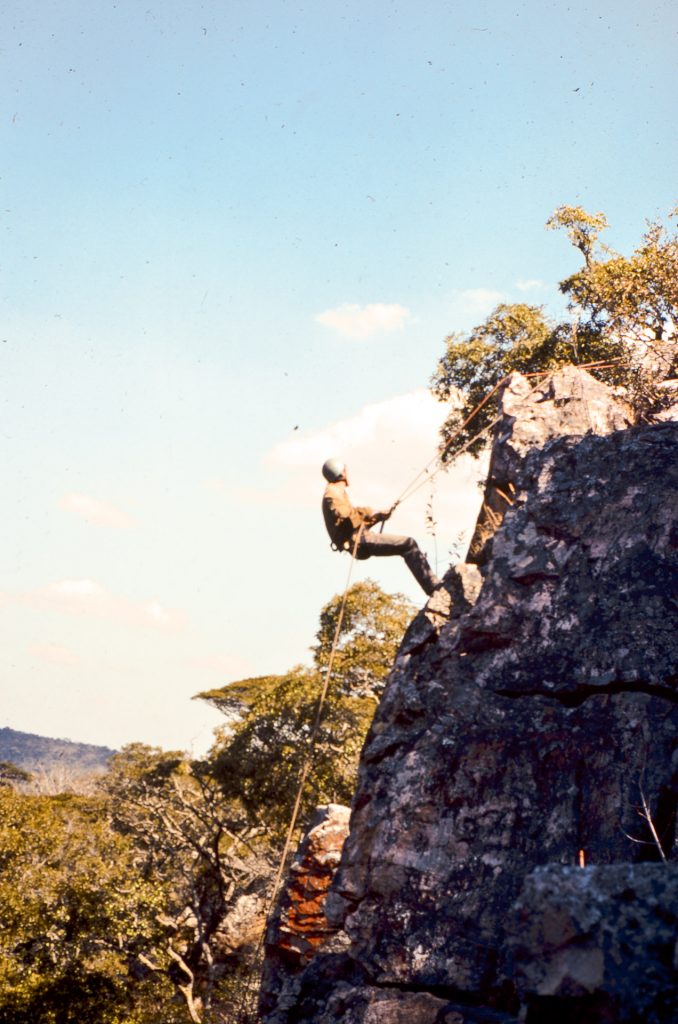

The rainy season in Luangwa led me back to Blighty and Moray House College at Edinburgh University, to do a teaching Diploma in Outdoor Education. This was a year of climbing, canoeing, diving, sailing, caving, skiing, orienteering, and walking, covering almost the whole of Scotland, the Lake District, Peak District with a final expedition to the Pyrenees.

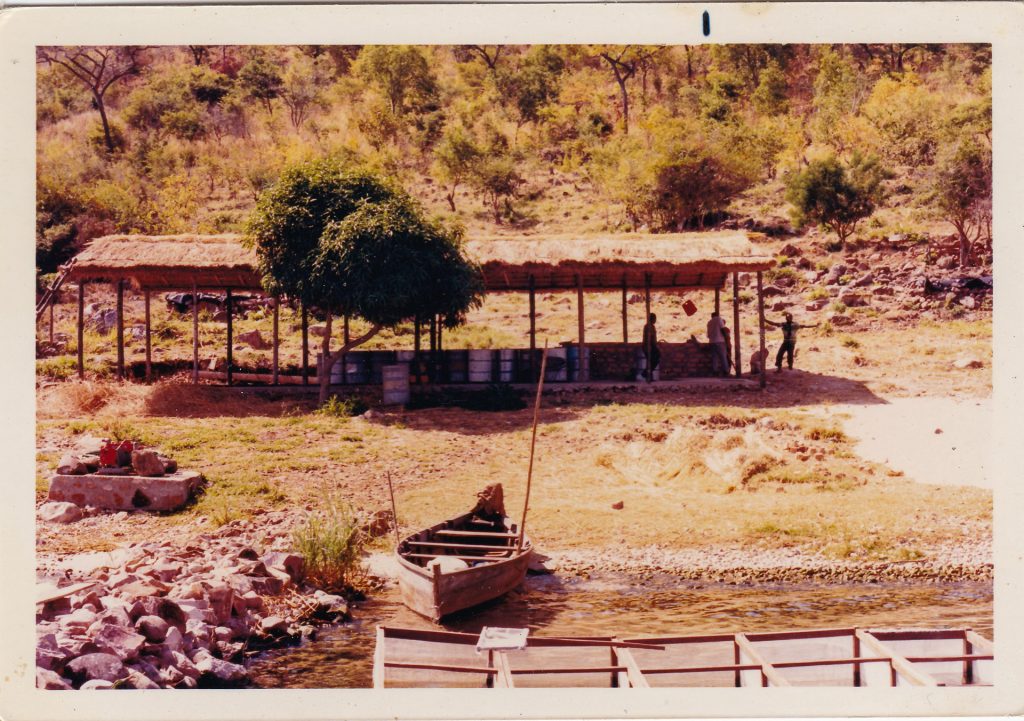

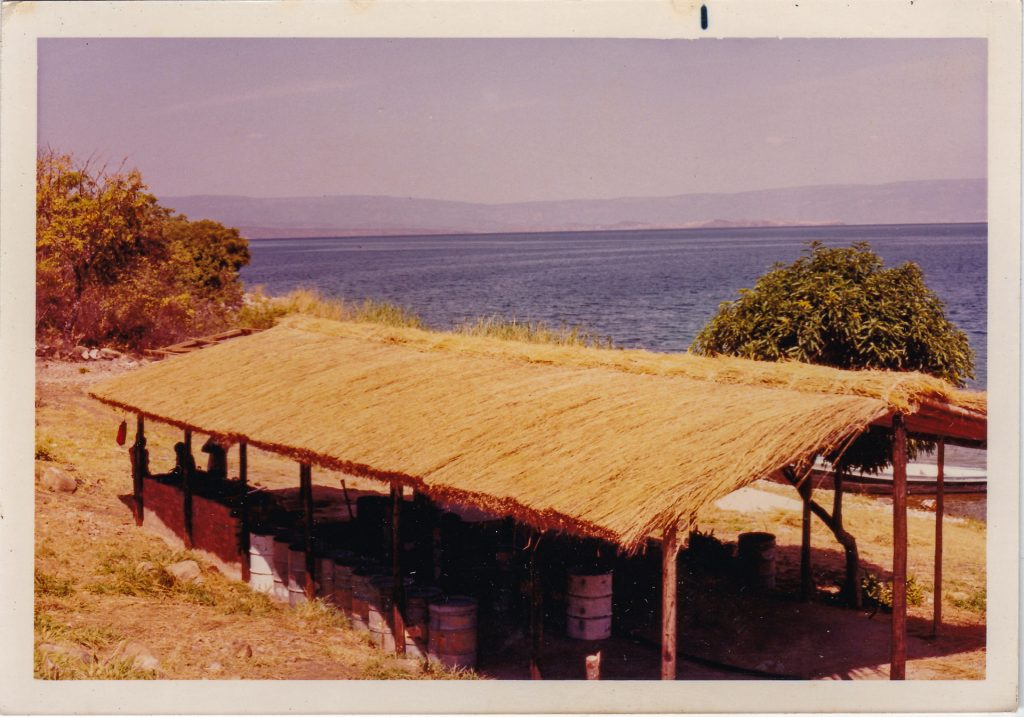

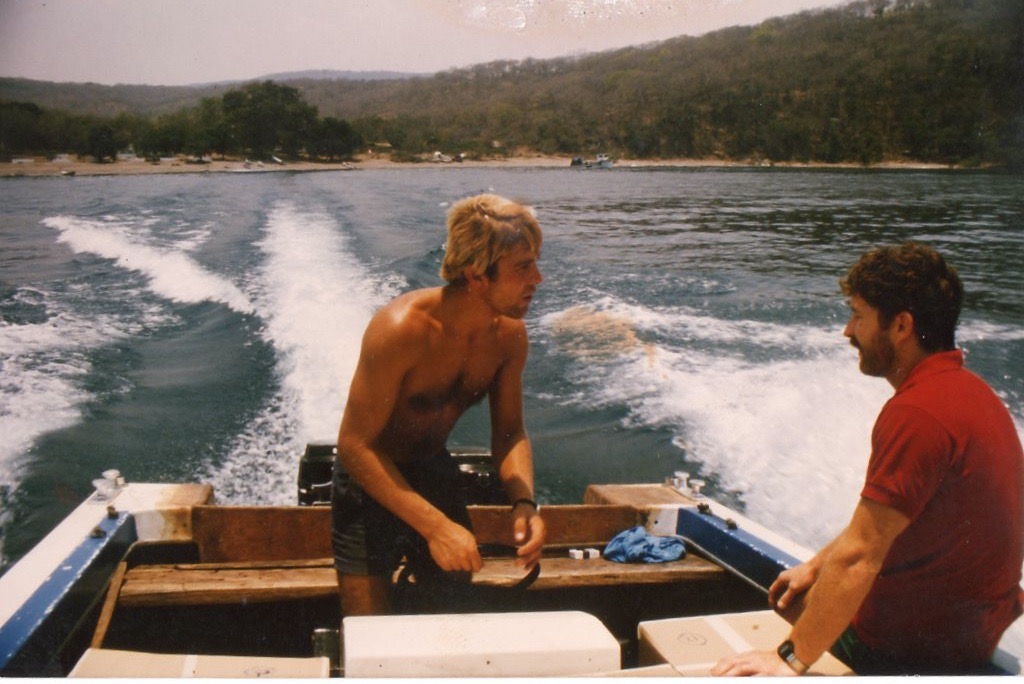

Another quirk of fate swayed my mind about what to do as I was finishing the course and working at an outdoor centre in Scotland, and I was offered a safari lodge to manage at the south of Luangwa National Park. Without a great deal of contemplation I decided to give it a go, I was missing Africa. It was soon fairly apparent that the venture would not get off the ground and I was about to head back home when I was offered a job on Lake Tanganyika which entailed diving to catch live tropical fish for export to the world-wide aquarium market, to help run a crocodile farm, and a small part in a commercial fishing operation.

The big attraction for me was exploring many many miles of the southern coast of this magical lake, both under the water and on the boat. Lake Tanganyika is a rift lake formed 15-18 million years ago, the second deepest lake in the world, and containing roughly 14% of the worlds fresh water. What fascinated me was the endemic lake fauna which had evolved over the millennia into a rich variety, the jewels in the crown being the endemic cichlid fish species. Charles Darwin and Alfred Wallace would have been in dreamland had either ventured there. With the ability to use SCUBA gear a whole new world was lying in wait. One of my most vivid memories was finding six unknown species in a couple of hours, it was an indescribable feeling with adrenaline and elation, heightened by the fact that we had deliberately strayed into Tanzanian waters with no passports nor visas.

Lake Tanganyika can be considered as a freshshwater inland sea, roughly 450 mile long and occupying a rift down the middle of Africa. Over the millennia I am sure that it has acted as probably Africa’s biggest and most reliable watering hole for a myriad of creatures, and has been key to their long term survival. I am also convinced that it played a major part in the beginnings of humanity, a history that has not yet been revealed because it is not does not provide ideal conditions for the fossil record in the same way that say, the Olduvai Gorge in East Africa does, nor have the same number of anthropologists investigating its past. I have never been convinced of the tree ape to bipedal savannah hominid tale that is commonly understood and presented. There are many more links out there that we have not investigated and explored.

The lake has played a role in the slave trade on both east and west coasts of Africa, and has been a major trading route in the interior for centuries, including food and supplies as well as gold, gemstones and ivory. A bizarre part of the 1st World War took place on its waters and along its shores. In many way it is a microcosm of the whole continent and the world, but its story has never really been told nor revealed except in fleeting glimpses. In popular imagination it remains part of the deep, dark, hidden, mysterious heart of Africa.

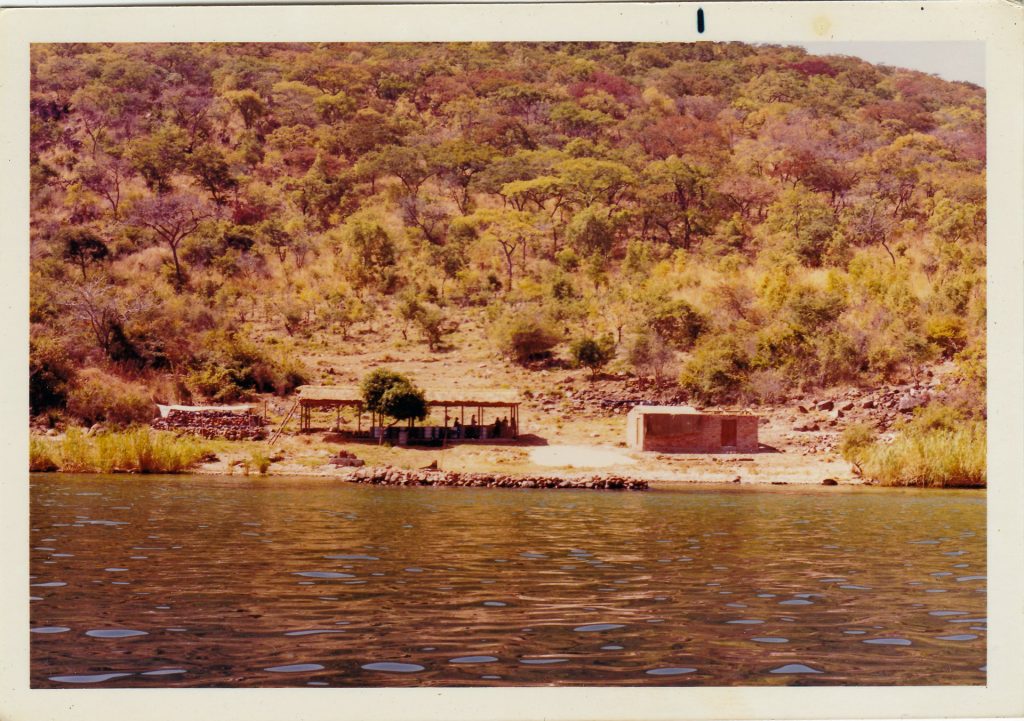

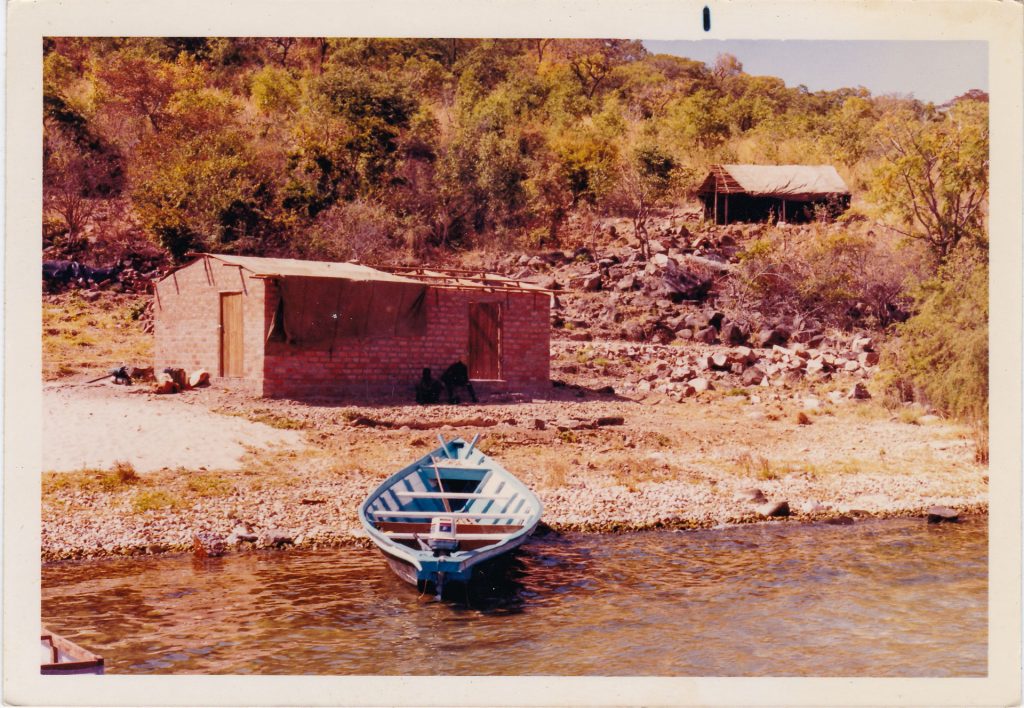

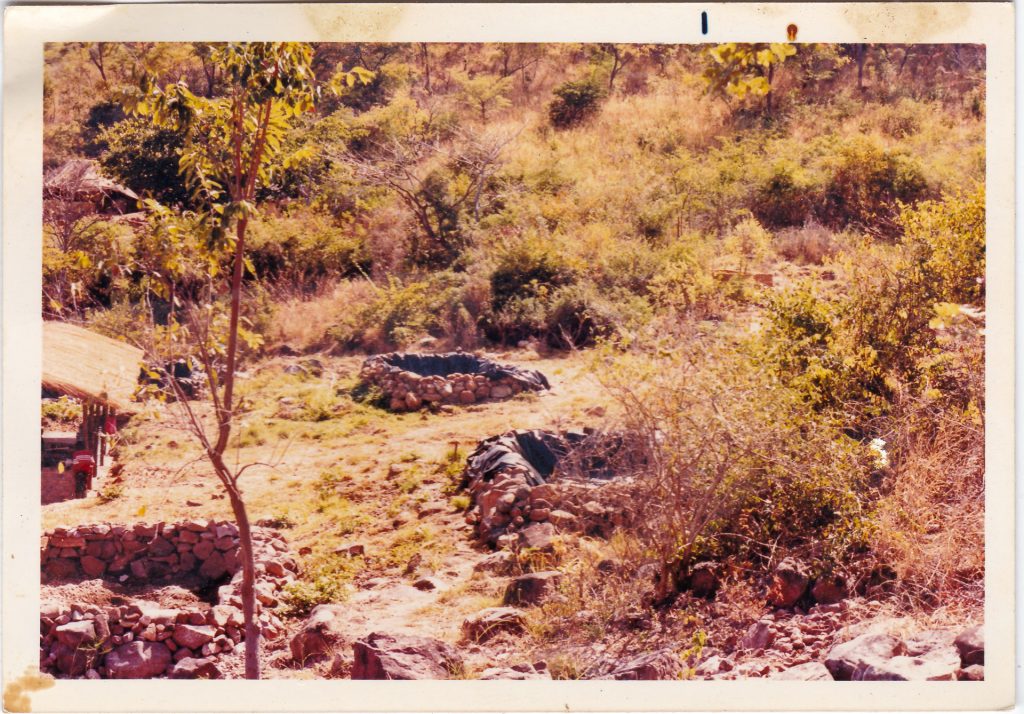

Lake Tanganyika had captured me and my imagination. A strong bond with the lake, its life and its people developed and grew over many years, and I felt deeply rooted there. I had started with some bare ground along the lake shore that had been a seasonal fishing camp, and cleared of many trees to plant cassava, and then left to recover.

It grew into a business which involved catching, acclimatising, breeding and exporting live fish for aquariums all over the world, with two bases, one in Zambia and one in Tanzania and was employing close to 60 people.

Time flashed by, building and developing the place, and exploring the lake, logging up more than 5,000 dives, several new species of fish, as well as venturing into lots of other parts of south and central Africa. It was a period with many tales to recount; being shot at by Zambian game rangers armed with AK 47’s (in error), arrested and locked up in Congo, underwater encounters with hippos, crocs and water cobras, emergency landing in my plane in the middle of the Bangweulu swamps, attacks by soldier ants, lake storms, armed break ins, boat sinkings and strandings, crocodile culling, sailing a small fishing boat around the Cape of Good Hope to then bring by road through Tanzania to the Lake, to name but a few.

A small tourism business was slowly growing with research groups, aquarists, divers and film crews. I was just about to start an aquaculture project growing an endemic species of fish in cages on the lake, with a fish that had never been cultivated before in this way. It was all pretty exciting stuff, and it was certainly an outdoor lifestyle that I fully enjoyed, whilst being very demanding in lots of different ways, with many adventures and experiences, trials and tribulations, all mixed up with with bouts of malaria and the odd dose of dysentry. What came up next made dysentry seem like a Butlins holiday.

It happened in a split second, a small group of us relaxing, enjoying a lazy Sunday afternoon, enjoying the crystal clear air with stunning views over 60 miles away into the Congo and the occasional dip into the lake. My wrist was suddenly grabbed and I was heading over the edge of the jetty wall into the calm, clear shallow water.

Little did I know then, it was the last dive I would ever make into those waters after many thousands, into that entrancing, beguiling, magical underwater world, and the last time I would see That Lake, and my home. A large white boulder was just under the surface and as I went in headfirst I tried to avoid hitting it and twisted my head, I felt a massive blow to the back of it, stars flooded my brain and then a white fog, I was lying face down in the water. Nothing happened, nothing moved apart from some limp, jellylike movements in my arms. Time stood still. Some hands came from nowhere and grabbed me dragging me to the shore with blood streaming out of the top of my head. I knew then that I was in serious shit. Right up to my neck in deep, sticky, stinking stuff!

Two days later, after a boat journey lying paralysed on an old wooden storeroom door, a bumpy ride in the back of a pickup van, a night in a local African hospital with paracetamol as painkillers, two medivac flights, I arrived on the tarmac at a small Johannesburg airport with only my underpants and my wristwatch. Lying on a stretcher waiting for an ambulance to arrive to take me to the hospital, the paramedic offered me a smoke and said, “Where you’re going mate, you won’t be smoking for quite a bit.” It was my last cigarette, but as a way to quit smoking it was brutally effective. 24 hours later the MRI scan showed that I had broken my neck and I had now officially entered the world of paralysis and life on two wheels.

A few months later, after a fortnight in neck traction staring at a picture of Mowgli on the ceiling above my bed in the old children’s ward, vivid morphine dreams, a neck bone-graft from my hip, two operations on a massive pressure sore that had developed at the base of my spine that you could put your fist into, blood transfusions, the Icelandic volcano ash cloud, and more, I was finally deemed able to be flown back to Blighty. It was the most expensive flight that I had ever been on and also the most bloody uncomfortable, strapped onto a wafer thin, rock hard stretch-er perched on top of the back seats of an Airbus. The airline food was not great either.

On arrival I was taken to Hereford hospital to spend a couple of months before there was a bed available at the Midlands Spinal Injury Centre, where I was to spend the next seven months, firstly to let the pressure sore heal a mind bendingly slow process, and then embark on a period of rehab and the start of a new life in a wheelchair.

In June 2011 I moved into a council flat in a small spa town in mid Wales, and I suppose that it was only then that a real degree of reality began to sink in about what had actually happened. Over the next 2 to 3 years the idea that I would become bipedal again and go back to my old life, and back to Africa and Lake Tanganyika became a distant dream rather than a reality. I had lost a way of life that had been rich in experience and learning, and whilst I had faced many challenges and frustrations over the years I had never been bored. I had also lost a business with a fair bit of boodle.

As this new reality slowly seeped in, I realised that this small, square flat was probably going to be where I would be spending the rest of my life. It was a prospect that I had never remotely considered so it seemed there was a choice to make: to either explore the contents of as many wine and whiskey bottles as possible, or else find the things that I could still do and enjoy, and find new ways of doing them. It was a question of trying to polish a steaming great turd.

Three years ago work slowly started on a garden, as a form of rehab, for both the mind and the body, a kind of existence-sustaining soul food. Ever since then it has been one of the central sustaining cores in my new life sitting on my arse on two wheels, and helps to make some sense of it all. If you are in the shit you might as well make the most of it and and try to grow roses and blog about the state of the compost heap!