I first moved into the flat in mid Wales nearly 17 months after the accident. I had been transported by water, land and air. Home had been a number of beds in different units in a variety of hospitals: Mbala to a Lusaka clinic to Johannesburg Millpark ICU, HDU, rehab then to Hereford and then on to the spinal unit in Oswestry, from where I emerged in a wheelchair to face a whole new world on two wheels in June 2011.

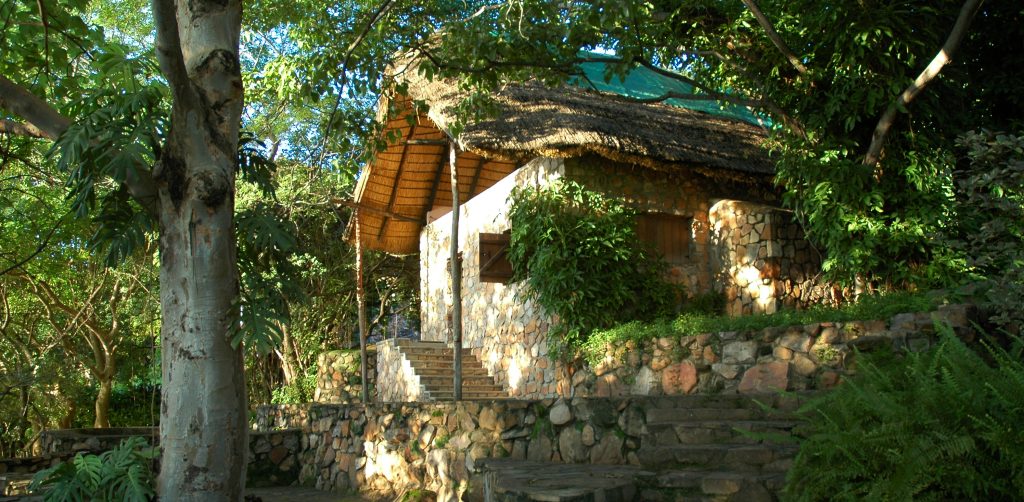

I had very few feelings about the flat and simply regarded it as a staging point to continue rehabilitating as I still imagined that since my neck break was technically ‘incomplete’ there was still a chance I might walk again and I would go back to resume my life in Zambia. It was simply a box with some rooms, a long way removed from my simple thatched house on the lake with its stunning panoramic view across Lake Tanganyika that I used to wake up to every morning with the first light of dawn.

The way that we normally regard injuries and ill health is, we break something or get sick, it gets fixed with the magic of modern medicine and the mighty NHS, we recover and then we go back and start where we left off, hopefully a tad more thankful and wiser.

Having spent over 20 years in Africa it is fair to say that I had had more lives than many cats would ever dream of having. I had developed a high risk lifestyle and it had become part of my DNA, which I think I tended to regard as completely normal. The thought of a 9-to-5 job, Monday to Friday was something that had never held any appeal and I had avoided for most of my working life.

The way that we normally regard injuries and ill health is, we break something or get sick, it gets fixed with the magic of modern medicine and the mighty NHS, we recover and then we go back and start where we left off, hopefully a tad more thankful and wiser.

Gradually one year stretched into two and then three. Reality slowly seeped in that firstly I was not going to be able to walk again, and secondly that it would be an impossible task to go back and resume my old life. Thankfully I had managed to pass a lot of time reading a whole variety of material on the internet and a whole bunch of books, and I was trying to get my mind as well as my body adjusted to the new parameters.

I was able to drive a car with adaptations soon after my hospital escape so I could to get out to various places a few times a week. The other residents in the adjoining flats had very kindly left the parking space nearest to my flat free for me to park so that I can open the driver’s door and get myself in an out of the car without being blocked in. Every time I drove back into that space and was unloading the wheelchair I looked across to the area in front of my flat.

What stood out above everything else were the shiny silver galvanised metal poles that had been put either side of the path leading to my front door which were meant to stop me from falling off the path. I am unable to walk, my legs are immobile appendages. The railings came to emphasise and symbolise my paralysis. They were ugly glittering signposts, only lacking neon lights, to tell everybody who walked past that somebody disabled lived there.

In the life I had left behind, I was probably seen and known as the mad mzungu from Tukulungu who had a fast fibre boat and dived in the lake with crocodiles, hippos and water cobra to catch live fish to export far away.

I had arrived to live and at the flat knowing virtually nobody, I had no provenance. I was simply a middle-aged man in a wheelchair with the shiny metal railings outside his ground-floor flat.

I asked the Council on various occasions if they would kindly remove them as I hated them and were of absolutely no use. I was told by a variety of people from different offices that they had to be there for my own safety. This sounded like a pile of old bullshit to me. Health and Safety had not reached the shores of Lake Tanganyika.

One June weekend three years later I called a friend with an angle grinder and asked him if he would like to put it to good use. A couple of hours later the bloody railings had gone and were stored neatly under my front window where they stayed awaiting collection for many months.

Once the scaffolding had gone, other things began to change and to come into being. It was in June 2015 the conscious effort to start a garden began. It was also the month that a twelve week old ball of caramel coloured fluff in the form of a puppy arrived in my life, for better or for worse.

Today it is really becoming a home to enjoy being in and part of. I have a comfortable sense of being rooted and immersed in a space that I now enjoy waking up to, grateful to be alive. I still miss that magical lake, with all its life and moods, carved out in a 420 mile long rift in the heart of Africa, but, thank goodness the bloody scaffolding disappeared.